Hope International wanted to do something powerful – a film about the savings groups in East Africa, and the personal stories of the people who organize them. Instead of a traditional commercial, we teamed up with them to create a short film based on a true story, with Michael Rothermel directing.

It was one of the most ambitious, risky, and rewarding projects we’d been involved in, and it immediately presented a host of creative challenges, starting, as everything does, with the script.

The Script

Writing a script is always tricky. You either have something defined to convey – a mood, a message – through the medium, or you’re wrangling the required structure in search of a feeling. Building the framework a film will be hung from is a complicated process for even the simplest of films. It’s even harder when you’re telling a true story.

When we sat down to write a short film to be shot on location in Rwanda, we were unbelievably excited, and determined to do the subject justice. We settled on telling the story of Aline, an incredible young single mother and entrepreneur. The story of her immense heartbreak and equally immense courage made a perfect story, eventually.

But it was also one of the more revision-heavy, grueling writing processes we’ve gone through.

Writing the Personal

The script was a collaboration between Michael Rothermel, the director, and me (hello!), the scriptwriter. When I sat down to put our plan to paper, I was determined to tell Aline’s story respectfully and with heart, to honor the real-life person who had been vulnerable enough to share her story with us.

I’m not a woman, not a teenager, not Rwandan. I’m not an assault survivor and I don’t share many of Aline’s obstacles. So I was determined to remove myself from the equation. I wanted to be sensitive and respectful, culturally and personally, and not allow my own experience of the world to shade the film. With the help of Andrew Bilidabagabo, the producer and a native Rwandan, I wanted to scrub myself completely from the script I was writing.

Which is obviously impossible.

After weeks of work, we had a script that systematically hit the beats of her story, accurately and efficiently. The producers, Josh and Andrew, sat us down and told us (gently) that the script wasn’t working. They didn’t feel anything when they read it. There were no moments that stuck with them. It was functional, but bland. And a bland script is about as bad as no script at all.

After staring at the wall for a few minutes, we hit the whiteboard and cut the story down. It didn’t need to be a recital of events, it could just be a few moments carrying one emotional thread. And so what had been the middle beat of our script was expanded to become the entire thing.

We’d given ourselves the ability to slow down, to feel alongside Aline at her lowest point, but that didn’t solve our emotional problem with the script. It still felt detached.

I went home from that meeting and realized I’d been writing it all wrong. I’d been forgetting everything I knew about finding feeling in a story. I didn’t need to keep Aline separate from me; I needed to find myself in her story, just like the director and the actor would need to find themselves in her story, in their turn.

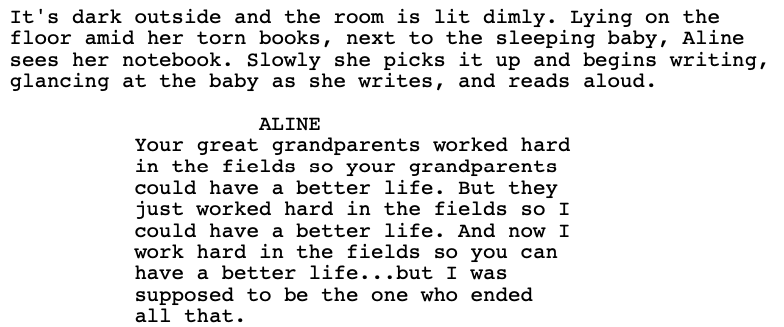

That night I went home and wrote these lines:

This was the part of Aline’s story that I knew, deep down, because it also felt like my story. And once we had that feeling down, the rest of the script came into focus. Her desperate love for her daughter. Her grief at fading dreams. Her love for and contention with her mother.

A script is only, at most, a recipe. The power of the film is filled in as each person brings their own meaning to it, as each person finds themselves in the story. The scriptwriter only gets to take the first turn.

But if you’re starting with an unfeeling, impersonal document, it makes everyone’s job of finding the feeling a lot harder.

We learned, or re-learned, from the process of writing this film that all creating is personal, and reveals something about the creator. Perhaps that’s a limitation at times. But it’s also why creative work has any power at all.

Why it Matters

The kind of detachment I nearly fell into is especially easy when you’re making something with a goal, like a commercial, or an awareness film. But the heart of a film – any kind of film – comes from finding moments of specific feeling, because feeling in the creator translates to feeling in the viewer.

And feeling in the viewer is power.